Several times, during the last months, I felt that I wanted to write an article about the city of Timisoara, Romania, and competitiveness. I postponed my wish as elections for the consistory were to be celebrated at the end of September 2020. I preferred to wait till the new team were sworn.

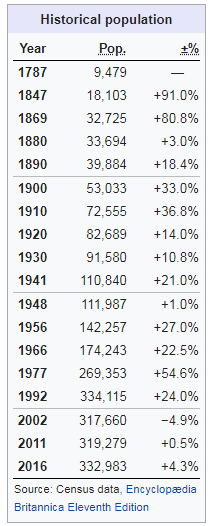

Timisoara is not a large city, thou it is among the largest in Romania. The total population is somewhere between 320.000 and 350.000 people. It is on the Western edge of the country, not far from Hungary and Serbia. It is considered prosperous when compared to the standards of the country, has several universities, plenty of industry, an international airport with many destinations, and history that retrocedes 1.001 years in time, to 1019.

Why is Competitiveness important for Timisoara? Because as the WEF says Competitiveness is how countries create the best social, economic and environmental conditions for economic development, striving for Competitiveness is striving for rising prosperity. Every company, city, region and country should make all necessary effort to increase its Competitiveness.

Competitiveness is not about producing or selling cheap. If this were so the most competitive countries in the world would be the poorest, and it is exactly the other way around. There are many definitions of Competitiveness. I created mine, which is: Competitiveness, the quality of being wanted despite the costs.

A competitive city is one where people are happy to live in because they perceive they can enjoy a good quality of life enjoying good jobs, a healthy environment and a rich social life. In an open world, cities compete among each other in search of talent, investment, population, wealth and capacity of influence (Power).

International institutes measure Competitiveness thru economic and social indicators but also asking the opinion of those living in the countries. Opinions are made of perceptions. This is why it is of significant importance to keep an eye on the perceptions of the people. A good perception is a push forward; it can start a virtuous circle.

I mentioned before the words “influence” and “Power”. The idea of Power is crucial because the search for Power is the real engine of human society. Power is linked to survival, and the struggle for survival is our most inner instinct. Today, cities are already more important than regions in many developed countries. During the last decades, a well-managed city has seen its power and influence grow, poorly managed cities see their strength going down the drain. Not understanding these movements can be an obstacle in the road for a good future. Deprived of armies, cities can only deploy a wide range of soft-power policies to increase their influence, and Competitiveness (the quality of being wanted despite de cost) is one of them.

Is Timisoara competitive? In what frame? Compared to what other cities? Could it be more competitive? How?

Timisoara is one of the most competitive cities in Romania, but this is not something that can content us. Timisoara is not competing within Romania. We need a broader image, the real one: Timisoara is competing in Europe and the world. Cities in the 21st century need to think globally because markets are global, companies are global, and citizens are global. There is no point in being the most competitive city in Romania if it is not competitive when compared with other similar municipalities in the rest of Europe and beyond.

So let’s start from the beginning.

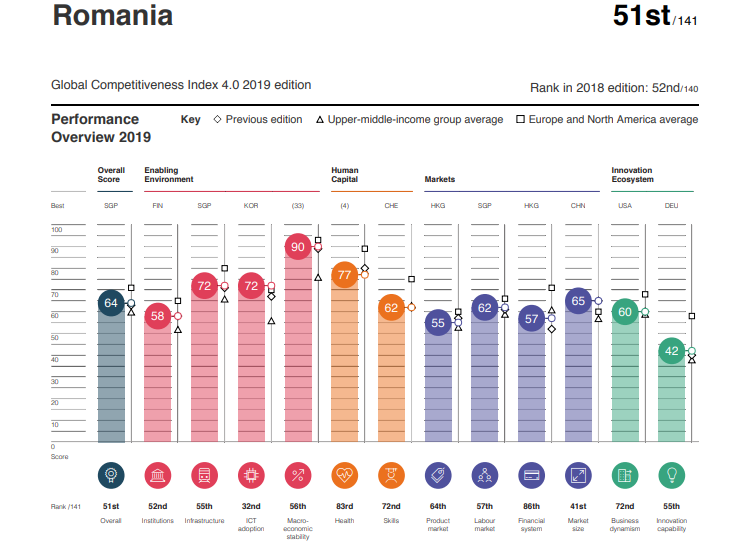

What competitiveness position occupies Romania in the world? According to the Global Competitiveness Index 2019, Romania is placed in the position number 51 out of 141 countries.

Is this important to our analysis? Yes, the Competitiveness of the country affects the Competitiveness of the cities and regions in it. Romania is a centralised country in which the most transcendental decisions are taken by the Government in Bucharest. Besides, the reputation of a country will immediately be mirrored in the reputation of its cities.

Let me give you an example: I might have doubts about the Competitiveness of two unknown (to me) cities, Tanchon and Yongin. Still, if I find that the second is in South Korea and the first in North Korea, I will immediately think that Yongin is more competitive than Tanchon because of the different reputation of these countries.

Timisoara is in Romania. The reputation of Romania, regarding Competitiveness and not only, will have a direct effect on the perception of Timisoara. Improving the Competitiveness of Romania improves the Competitiveness of Timisoara and vice versa. They need to take care of each other because as said, Competitiveness is also a matter of perception.

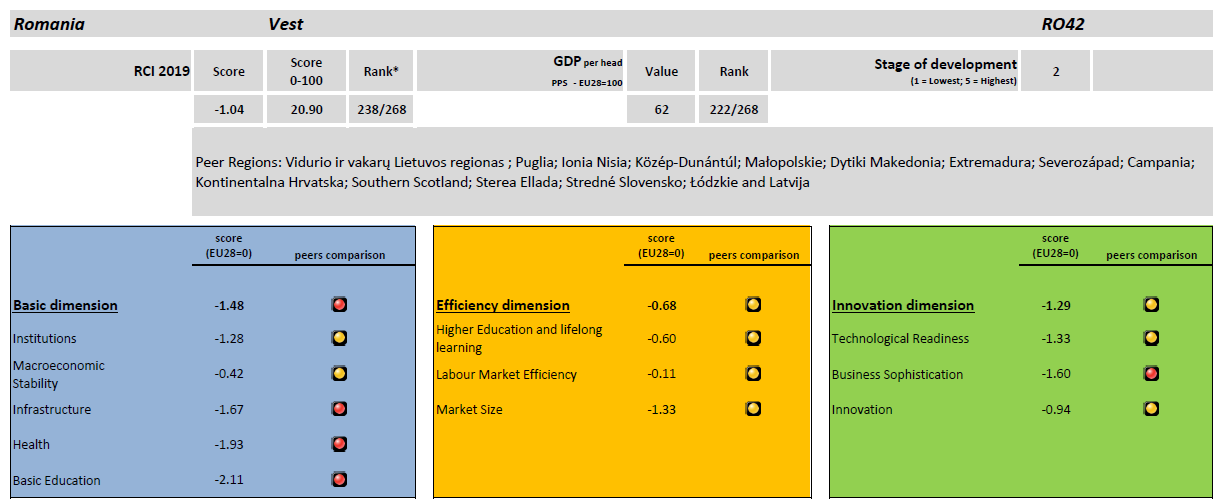

Timisoara is the capital of the Timis province. There are 41 provinces in Romania. We do not have competitive comparisons for each, but we have them for the regions. The EU has considered the analysis of 268 regions across 28 EU member states for 2019. The resulting report of this analysis is called “The EU Regional Competitiveness Index 2019“, and the 268 charts are found here. Romania is represented by its seven regions plus the area of Bucharest. The region called West includes four provinces: Timis, Arad, Caras-Severin and Hunedoara. Timis is the richest, while Arad is very well developed too.

According to the European Commission, what is the competitiveness of the West region in Romania?

As can be seen, the position of the region is not extremely favourable. It is listed in a very much down in the ranking (position 238/268), and thou it is true that Timis is probably the best of the four provinces, there is room for improvement.

We do not have a competitive ranking for cities. Still, we can get a feeling when compared with other European cities of similar size.

How can we improve the Competitiveness of a city?

In the Global Competitiveness Index, the World Economic Forum analyses countries. One of these countries, and the most competitive one, is also a city: Singapore. So, in theory, the same parameters used to score Singapore could be used to value other towns. In theory. The reality is that the government of Singapore can decide on all the matters that count in their tiny state, which is not a capacity of most mayors in the world. Still, these have some degree of decision. One first approach to value the Competitiveness of Timisoara could be to take the list of parameters, tick those where the local administrations have a word to say and value them. Local administrations have a lot of capacity to change, for good and bad, the quality of life and activity of people and companies. Local hospitals, air pollution, schools, electric, gas and water supplies, regional airport, international projection, bureaucracy, entrepreneurship, almost everything can be touched.

This would be a clear, accessible and straightforward approach, and a group of people could be appointed to monitor the improvements in this respect.

We can also consider looking at the experience of others. Some papers can help us understand how countries have tried to boost the Competitiveness of cities and maybe take them into account.

A very appropriated one is “Competitive Cities in the 21st Century, Clusted-based local economic development” (KyeongAe Choe and Brian Roberts for Urban Development Series, Asian Development Bank)

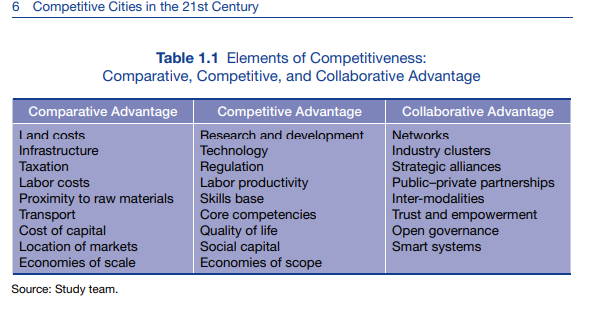

According to this research “national governments cling to the notion that the economic development of cities and regions rests largely on supply-driven physical infrastructure”. The authors consider this view as an “old way of thinking that thwarted attempts to improve overall economic performance”. KyeongAe Choe and Brian Roberts present three approaches by which states can improve their cities’ Competitiveness.

A few lines about each:

Comparative advantage: Towns and countries that develop a Comparative advantage tend to induce specialisation as it seeks to achieve Competitiveness by keeping production costs (labour, materials, energy, taxes and infrastructures) low.

This has been the guideline implemented by Eastern European countries, including Romania: investment would flow in because labour was cheap and the infrastructures were good enough to permit the export of production within hours to their final destination. In the case of Timisoara, this was a right starting approach in a moment when foreign investment was very needed, but this advantage works for as long as the populations are poor. It is true that many firms, mainly from Germany and Italy, invested heavily in the city and metropolitan area because of abundant, very convenient labour and short distances to those countries. And then something started going wrong. The same way that destination markets are near Timisoara, also many better-paid jobs are near Timisoara. Thousands of people left to the West attracted by the promise of higher salaries and more functional societies, a few hours away by car. The result is a lack of workforce which has pushed wages up. Now Timisoara has almost zero unemployment. Salaries are high, and also land costs and industrial spaces are expensive. The company who wants to produce cheap can find much better elsewhere. At least, its excellent geographic position has not changed.

Competitive advantage (Porter 1985): “Emphasises efficiencies in the means of production, mainly in so-called value factors that have to do with performance and quality, using advanced technology to increase productivity”. In a scenario in which the population is neither impoverished nor abundant anymore, in which “quality of life, human capital and social capital” are considered key factors, the competitive advantage represents a step forward. In my conversations with some producers in the automobile industry in Timisoara and its surrounding area, significantly impacted by the lack of employable and stable workforce, they pointed out the need to invest in more advanced and performing machinery to reduce the dependency from employees. This approach would lead to smaller and better-paid staffs, with growing productivity and higher levels of satisfaction. As a downside effect, there is a possible increase in unemployment as machines replace people. Still, it opens the door to new high added-value job profiles in areas such as IT and R&D: the road to take. It would be indecent, in the long term, to rely on the poverty of the population to bring investment. Authorities and firms, on the one hand, need to set policies leading to increase local productivity; on the other hand, they should provide training to those in need of a new professional profile. In Timisoara, the Competitive advantage is still in an initial phase and for sure will develop strongly. I suppose that automotive industries are planning the effect that the rampant success of the electrical car will have in their production sites before making expensive invetments.

Collaborative advantage: “For companies that crave success in business or governments that hope to entice investors to invest in local economies, comparative or competitive advantage is no longer enough. … Former rivals are seeking to collaborate to win and expand their business”. Companies aim for improvements in costs of R/D, production, resource efficiency, sales, and so on. The cooperative mentality is not widely spread in ex-communist countries. Cooperatives and other forms of associations bring Romanians the memory of the forced collectivisation of the old regime.

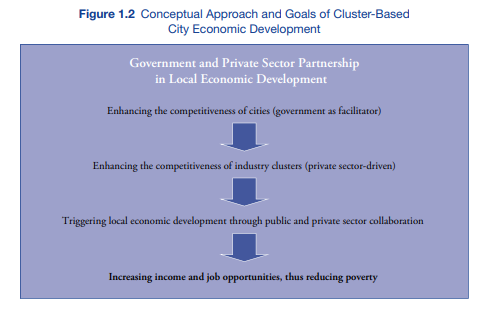

Nevertheless, exist some few examples of success. The NGO ADR Vest (Agentia pentru Dezvoltare Regionala Vest) has initiated three different clusters (technology, IT and automotive) to support the economic activity of companies in the region and push for higher degrees of collaboration among all interested actors. It is an excellent example of how to boost a collaborative economy, but it is not enough for a city the size of Timisoara. IT and automotive are key local sectors of activity; still, other industries should also be able to join in cluster-like structures to achieve growing synergies.

KyeongAe Choe and Brian Roberts confer significant importance to the development of clusters and collaborative advantages. The role of the players is evident in this chart:

These three types of “advantages” are not mutually exclusive. Societies do not need to abandon one level to step onto the next. As the city evolves, its economic activity should naturally move towards higher degrees of sophistication. The trend should be to proceed from comparative advantage to competitive advantage and, finally, to collaborative advantage. Collaboration is the magic word and team-work the correct attitude.

The case of Wichita (Kansas, USA):

Many cities have faced situations in which population was going away, the local industry was in jeopardy, and there was a certain disenchantment in the air.

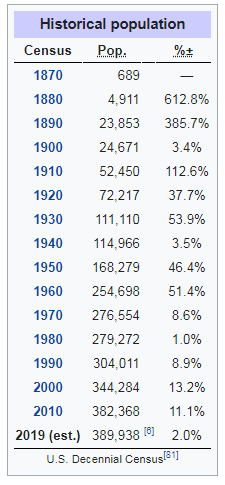

(The case of Wichita has been analysed by The Chung report) Wichita is a city in Kansas (USA), with a population of 385.000, comparable in some aspects to Timisoara. Both cities faced or will face similar problems. Kansas is almost the size of Romania, but the population is short under 3 million people. At the time of the analysis, the Wichita population growth was slowing down because of better opportunities in other cities. The number of households was consistently falling, and thou there was a certain amount of newcomers, they do not number enough people to fill up the gap. An additional problem detected in the period 2011-2013: the households that left Wichita were making an average of 70.000 $/year while those arriving were making (only) 58.000 $/year. The “Population challenge” meant that, if not reversed, firms would face problems in hiring performing workers. The workforce is a vital input for every company, and its absence can result in companies moving out.

Something similar is happening to Timisoara. The population seems stable, but the undertide movements are in a constant flow: Workers come and go. Many companies express their concern about the lack of workforce and their problems to retain talent. As a solution, many of these companies brought employees from other parts of the country. Unfortunately, it did not work as expected. More often than not, these newcomers were resigning right after the training or after a few months of experience and moving to countries like Germany. The Covid-19 might temporarily change this situation as also Germany and other Western economies see their unemployment rate grow. Still, as soon as a new frame of economic stability appears, Germany (and others) will request a foreign workforce to face the challenge of their ageing population.

To my surprise, there has been a real lack of interest from all the parties, in the private sector and the public administrations, to solve the issue. Each of them wants the other to find and apply the solution. Let me explain: during years I attended meetings in which the company managers were complaining about the lack of workforce. I retained an estimate made by a qualified source that claimed that companies in Timisoara needed between 10.000 and 15.000 workers. The 1% unemployment rate in Timisoara was contemporary with 15% or 20% unemployment in other regions in the European Union. Timisoara is a charming city, friendly to foreigners, well communicated by air, with low costs of living and salaries now comparable to those in regions with high unemployment in Spain or Italy. In 2018 I developed a plan to cover the workforce needs with unemployed people aged over 50 from Western countries. Managers told me that age was not a problem for many Timisoara companies. People over 50, still fully capable of productive activity, do not have many chances to find a new job when unemployed in Spain, Italy and other countries even though they are stable and experienced. Timisoara could offer them a chance, and not only for them but also for their spouses. These couples, often with grown-up-independent kids, could be active again. Their joined income would be high enough to pay their lodging, make a good life and build up a saving account while feeling useful again. Besides, being EU citizens, they would not have any problems to start working very soon after their arrival.

I spoke with the employment responsible for the government of the region of Valencia. He fully supported the idea. I found that there were more than 150.000 people over 50 years of age registered as job seekers in that region. Could we find 10.000 people willing to come for 1 or 2 years (more if they wanted) to Timisoara to work? I think so. Of course, these people would not fix their residence in Timisoara for the long term. Still, they would be a big push forward for the local industry which needs responsible, stable staff. The idea seemed straightforward, but there was a problem: Housing. Coming for a relatively short period, they would have needed this issue to be solved for them, preferring to be close to each other, talking in their language and organising their free time together. A non-conflictive group of adult people could be a solution for the industry and also a new source of prosperity for many sectors (tourism, restaurants, shops, airport,…). With this idea in my head, during 2018 and 2019, I met with the private sector and the public officers from all administrations. In front of the solution, no one did anything. The public sector applauded the idea but said that they could not provide housing for non-Romanians. That is not what I was asking. I just needed their capacity to gather companies in search of the workforce and make a joint presentation. I also expected from them facilities that could be adapted by third investors or the own interested firms to accommodate the newcomers. Long term concessions of public soil for lodging were also an option. All this was possible. Rather, they acted as if it were not their problem. Still, it is: fewer workforce means fewer jobs created, fewer taxes collected, less economic activity, fewer companies willing to invest, less international presence, and so on. Besides, Timisoara could have gained a considerable amount of notoriety and image in Europe, as a city helping to solve an enormous European problem as is the unemployment of people over 50. Timisoara again as a model for many other cities. The business people I met, those continuously crying that they need solutions (from the government, of course), did not consider this though. I know why. Large employers in Timisoara are manufacturing units subordinated to offshore control; they do not retain the power of decision out from their production scheme. I know how these companies work because I worked for long years in one of them. Their managers will not take the risk of a mistake for thinking out the box. Proposing to their headquarters a lodging solution, whichever it might be, is a risk that could have negative consequences for their careers if something went wrong. Instead, complaining to the headquarters that they cannot reach production because there is no workforce implies no risk for them. In this second scheme, they pass the problem to the main office, which will have to decide what next, including the possibility of closing the premises, as has already happened. Many of these managers are in Timisoara for the short term, a few years only. They have no local emotive attachment, neither with the branch they work for (tomorrow it will be another) nor with the city. There is nothing wrong with this attitude. It is normal and just a variable to take into consideration. Still, a solution was possible in this case, and I remember this episode on the off chance it can be reconsidered.

So yes, Timisoara has a human capital challenge.

The consultants that worked the Wichita case identified other challenges for the city in Kansas:

- Entrepreneurship challenge

- Perception challenge

- Business cycle challenge

How do these challenges mirror in Timisoara?

The Entrepreneurship Challenge: Timisoara needs more entrepreneurs, more people to come with ideas and to risk their assets for those ideas. Timisoara had this entrepreneurial mass in the past, and still now. Throughout its history it has been a very dynamic city with very significant industrial and trade activity. The very same name of the Fabric quarter is proof of it. Many pictures of a pre-communist town show it busy with plenty of shops. Many citizens still remember the factories existing during communism. The current situation –conditioned by the future evolution of the pandemic – is not a disaster. Small street-level commercial spaces exist, and modern city malls offer a wide range of choice. Professionals in many areas have opened offices, and industries such as IT have shown tremendous strength in the city. Still, this is not enough. An entrepreneurial climate, which is now waning, needs to be boosted, and the local administration can be the key to achieve it easing the creation of a business by reducing the bureaucracy and accelerating permits and authorisations. Another measure is to offer direct support to those wanting to risk and conscious that they need assistance. We can find successful examples. Other cities that have created “Entrepreneurship incubators”, spaces where those willing to create a business receive training and mentoring. As an example, I can name Barcelona Emprenedoria, a proposal of the city of Barcelona that, during its many years of existence, has supported the private initiative and helped thousands of new entrepreneurs to fulfil their goals. For this, the city hall could find good support in the FEEA (Faculty for Economic and Business in the Vest University of Timisoara), which would be a plus for everyone (University, City Hall and entrepreneurs).

The Business Cycle Challenge: Many see a risk in a city so dependent on the car industry. It has been a key aspect of development for the whole region and a source of appreciable income for thousands of households. It has employed both high qualified workforce and thousands of non-qualified workers. But is moments of crisis and change, as the one that the automotive sector is going thru in Europe, this can become a problem. The ideal – and challenging- situation would be one in which diverse well-developed sectors of activity complement each other and serve as buffers for the business cycles that affect our economies. Business cycles are a constant reality. They are normal, and we need to understand them to be able to cope with them. What other sectors could absorb employment in case that the automotive crashes? Whatever is to be done, it must have a base on technology and research.

For comparison, I copy-paste, from Wikipedia, the article about the painful change experienced by another American city, Pittsburgh, where “Following the 1981–1982 recession, for example, the mills laid off 153,000 workers” (Wikipedia) after which they reinvented themselves: “Beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the steel industry in Pittsburgh began to implode along with the deindustralization of the U.S. Following the 1981–1982 recession, for example, the mills laid off 153,000 workers. The steel mills began to shut down. These closures caused a ripple effect, as railroads, mines, and other factories across the region lost business and closed. The local economy suffered a depression, marked by high unemployment and underemployment, as laid-off workers took lower-paying, non-union jobs.Pittsburgh suffered as elsewhere in the Rust Belt with a declining population, and like many other U.S. cities, it also saw white flight to the suburbs…Present-day Pittsburgh, with a diversified economy a low cost of living, and a rich infrastructure for education and culture, has been ranked as one of the World’s Most Livable Cities. Tourism has recently boomed in Pittsburgh with nearly 3,000 new hotel rooms opening since 2004 and holding a consistently higher occupancy than in comparable cities. Meanwhile, tech giants such as: Apple, Google, IBM Watson, Facebook, and Intel have joined the 1,600 technology firms choosing to operate out of Pittsburgh. As a result of the proximity to CMU’s National Robotics Engineering Center (NREC), there has a boom of autonomous vehicles companies. The region has also become a leader in green environmental design, a movement exemplified by the city’s convention center“.

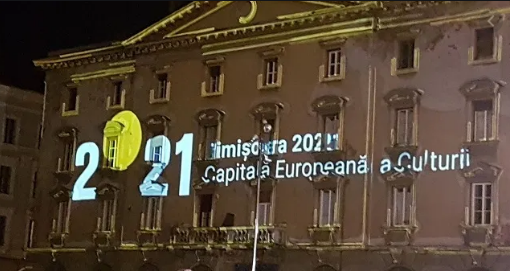

The Perception Challenge: “The City of firsts” “The City of the Revolution against Ceausescu” “Little Viena”, “A multicultural city”,.. all these and other are concepts and ideas linked to Timisoara. Important as they are, they talk about the past. None of them looks towards the future. A new idea has to be found. The European Capital of Culture project (initially scheduled for 2021, postponed till 2023 because of the Covid-19 pandemic), has not achieved to maintain the level of enthusiasm among the population that it enjoyed in the year of the designation, not to mention to increase it (multiple reasons, internal and external to the association, explain this failure). Anyway, in the best of cases, this is just a short term goal, with a fixed date that when surpassed, will be a pleasant memory. Timisoara needs a new moto, something that the city can identify itself with for the long term and use it as a leitmotiv for the many years to come.

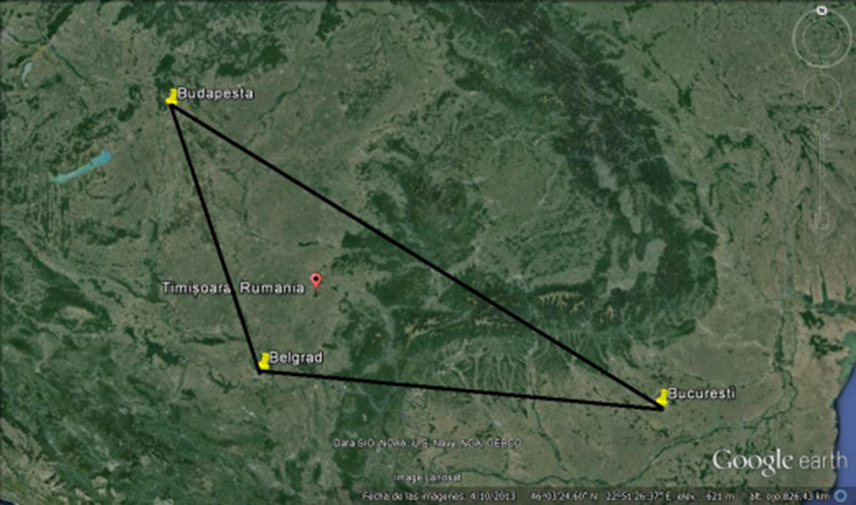

I like to think of Timisoara as “the Central city· I mentioned before that Timisoara occupies a privileged geographical position. See this picture:

Timisoara is the barycenter of the triangle formed by the lines connecting the cities of Bucharest, Budapest and Belgrade, capitals of Romania, Hungary and Serbia respectively. The barycenter is, in physics, the centre of mass. This position is, from a logistic point of view, of great importance. Timisoara is the city that, if it did not exist, should be created (or maybe the city of Arad would play this role): the optimal point where trade, traffic, warehouses, airport, even fluvial connections meet to serve a large territory. Timisoara should be booming with activity in a time in which cities gain more importance than regions and countries. The good news is that it can still be. We only need the ambition to be the Central City.

We could even go further away and notice how this central situation can be projected in all directions. A similar distance separates Timisoara from the Baltic Sea and the Egean Sea, the Black Sea and the Adriatic Sea.

How do we explain that Timisoara became such a diverse and multicultural city for three hundred years? How could it incarnate the spirit of living-together of the European Union two hundred and fifty years before its modern foundation? It was not a mere chance. Lucky events occur once, maybe twice, they do not survive for centuries. If Timisoara became a meeting point and a dwelling city for people of so many cultures, origins and religions, it is because of its position, of its central situation. Nowadays, to have a central geographical position is still important, but technology has changed the way we live. How can Timisoara maintain its prominent status beyond areas such as logistic or production? Only thru the ambition of achieving it: with intense research and development, high-level universities, an active civil society activity, a proactive administration, an ambitious private sector. The central position is still here, awaiting the attention it deserves from people, companies and authorities.

To complete the list, I add three more challenges that I see as necessary as the previous ones: The Environmental Challenge, the Civil Society Challenge and the European Challenge.

The Environmental Challenge: Timisoara has not put in place a conscious environmental policy. The previous local authorities operated under the premise that we live in the era of the automobile. This concept is, in the 21st century, out of date. Thou cars are and will continue to be important in our societies, the idea of cities built for car users does not find acceptance anymore and is to be changed. Cars find their meaning in long distances and exceptional cases, but other means of transport, including walking, bicycles and public transport need to play the role that cars were playing in cities. Timisoara is not a dense city. This has created the need for a very vast array of roads and the difficulty to plan adequated public transport systems. The result is the massive use of cars, but also a heavy load for the finances of the City Hall, which invests large sums in providing with services broad areas receiving very little taxes back.

An environmental policy starts with an urbanistic project that permits higher densities and the better use of scarce resources such as public transport, water, gas, electrical and internet installations, sewage, temperature isolation and so on. Growing vertically instead of horizontally is much more efficient from an environmental point of view and frees ground space for other activities. The proper management of local natural life is another part of this challenge as biodiversity, also in the cities, gains momentum. It has positive effects not only for the animals and plants that live in an urban environment but also for its people. Air quality levels, noise levels, stress levels, and all the different diseases resulting from an unhealthy environment are reduced when vegetation and wildlife gain room. The European Union is paying significant attention to this reality and supports policies that improve the sustainability of biodiversity in cities. The local administration has to be the motor for change and the European Union, the leading financial supporter.

The Civil Society Challenge: When I was in my teens, my home town, Barcelona, was appointed to host the Olympic Games of 1992. The amount of civil energy that this news unleashed was incredible. Once finished, many believed that the Olympic Games in Barcelona were the best in history and probably they were. There was a reason for that success: the volunteers. All wanted to participate and contribute to the success of an event that would put our city on the map: ” En torno a 35.000 voluntarios participaron en los Juegos Olímpicos y más de 15.000 en los Juegos Paralímpicos. Incluso hubo personas que se tuvieron que quedar sin poder participar.” (Around 35.000 volunteers took part of the Olympic Games ad more than 15.000 in the Paralympic Games. There were people who could not participate. Voluntariado y Barcelona, una larga historia) The Games meant a huge step forward for Barcelona on the international scene. This impulse has lasted for more than 20 years and created enormous wealth for the city (unfortunately, it came to an end when Catalan nationalism started dividing the population).

When Timisoara won the quality of future European Cultural Capital of Europe for 2021 (now 2023), I expected something similar but has not happened yet. I am sure that the will exists among the citizens, and this possibility is still there. Such events are nothing without the people behaving as motors. The citizens can be spectators, go to the shows or expositions. They usually do this. But considering the citizens as external to the organisation does not leave any long time mark. Under this perspective, Timisoara 2023 will only be something beautiful that happened, but not a landmark. The only way to impregnate the memory of the people, to unleash their passion and to make the utmost of a unique chance for Timisoara is thru an emotional link, to engage them in the process like volunteers, before, during and after 2023, to make them part of the success.

With this example, I stress an important point: In Timisoara, there is very little engagement from the Civil Society in projects thought for the good of the community. The question sometimes seems to be whether Timisoara has a civil society or only inhabitants. There is an active number of people ready to respond and get involved when necessary. Still, this number is small and needs to grow. Cities, where the population involve emotionally and actively, have more quality of life and are more competitive.

The European Challenge: Timisoara was the European Union centuries before this existed. Because of its geographical position, it attracted people from many different origins, cultures and religions. The inexistence of a linguistic or religious group with a clear majority among the population was a guaranty for a common peaceful life and prosperous business. This diversity, thou still present, has lost its balance in favour of the Romanian nationals, a phenomenon that occurred in all the countries in South-east Europe mainly after WWII with their respective national identities. There is no need, in the 21st century, of longing for a past society when nowadays the borders are much more fluid. Many young people already live in a multinational reality. They speak several languages, study in several countries and see their professional life linked to good career perspectives more than to their region of origin.

The European feeling might or might not be strong, but the reality is undeniable. Timisoara should try to play strong in this area by participating in as many international events as possible, abroad and organising them at home, physically or on-line. The name Timisoara needs to be much more visible and known. The Capital of Culture is an excellent opportunity, but there are many others. It is essential to gain weight internationally, to be present, to let the rest of Europe know about Timisoara and the citizens of Timisoara about the rest of Europe. Erasmus is another program that could be very meaningful; thou I have many reasons to believe that its objectives are not achieved in Timisoara. In what other organisms, competitions, conferences, meetings could Timisoara take part? How can it better cooperate with its twin cities? Could other cities twin with Timisoara? (I tried to twin Timisoara with Valencia. Valencia, which is much bigger, accepted. Incredibly all was stopped at the Timisoara City Hall when in reality Timisoara had much more to win than Valencia from this twinning). All these matters should be spotted, selected by their quality and addressed.

Timisoara and the province deserve to have a public administration aware that they are the starting motor of a necessary change. If they do not assume this role, it will be challenging to move forward.

Public administrations, because of their capacity to overview the situations, have the role of gathering the different actors and proposing solutions. They have to stop being part of the problem and become part of the solution. They are the primary impetus.

To celebrate that Timisoara is, indeed, one of the most competitive cities in Romania is correct. To numb ourselves with this is short-sighted. Timisoara is not as competitive as it should be at a European level, but has all the elements to become a real competitive city: Excellent position, plenty of space to expand, industry, universities, well prepared people, pleasant life, infrastructure, IT, potential volunteers, culture, history and hopefully the political will. We know that the effects of losing Competitiveness are not visible from one day to the other. Like a stone grinding a surface by friction, the damage can be appreciated in the medium term and it will happen if it is not reversed. We need to reverse it.

I have based my report on the city of Timisoara, but we could perfectly extrapolate it to the province if we wanted, even to the West region and to all Romania. They are not independent entities. What is good for one of them is good for the others, which implies responsibility, loyalty and cooperation in search of the common good.

I am confident because it is never late. Timisoara and Timis can and should do much better if they want to increase their regional role. Though we are not on the right track yet, we can for sure find it. Let’s give time to the new authorities, both in the City Hall and the province – and soon the new government -, to take over and work together for this goal. In times of crisis like the one we are passing this 2020, we all need to establish the bases of our future growth and identity. It is a challenging and exciting project at which all should be invited to participate. For Timisoara, Timis and Romania, the sky can be very blue.