Whoever gets into the concept of competitiveness will soon meet with different definitions of what competitiveness is. One thing seems to be the competitiveness of countries and another the competitiveness of an industry or company.

When talking about countries, according to the World Economic Forum, Competitiveness is how countries create the best economic, social and environmental conditions for economic development. They say that striving for competitiveness is striving for rising prosperity, creating more opportunities for all. You can access a youtube presentation at t.ly/Eppa.

Instead, when talking about companies, competitiveness seems to refer to the capacity of selling at lower prices than other firms. For many, a company is competitive if it sells cheap products.

Still, are we really talking about different things?

No, we are not. I have resumed “Competitiveness as the quality of being wanted despite the cost”, and this is valid in all cases.

Linking the competitiveness of companies to the selling price of their products is nothing more than a simplification. In the mind of the buyer, the price will be weighted together with the other features of the product. The quality of the good, the image, the name, the global perception that buyers and that the society as a whole will have of the item that they want to buy, will decide if it is competitive or not. There will always be cheaper products than the one we want, but we will opt for one or another depending on what we want it for. And only when all other factors remain equal (ceteris paribus), the price will be the final argument.

The perception is the image that our brain makes of something. It is our reality, only ours, not necessarily the general one or the one that best defines the product.

If the car buyer is ready to pay more for a Volkswagen car model than for a similar Seat model, even when they belong to the same manufacturer, they run the same motor, the are made with the same components and deliver very similar features, it is because the buyer perceives it as a better car (for him/her). And they probably believe that the rest of society does it too.

When a product is perceived to be good we expect it to provide the service we need. For many people, chosing a car is not chosing a mean of transport. They want that possibility, of course, but also many other things: a comfortable interior, capacity for more or fewer passengers, a larger or a smaller trunk, a particular colour, a performing sound system, many other available particularities and last, but never least, an extension of their personality and image. Many identify with their car and tell the rest of society “Do you see this car? This car is me (reliable, fast, aggressive, fun, modern, safe, expensive, nonchalant or other.)

All these qualities are not self-evident and need to be advertised. If they were, companies would not spend billions of € every year to communicate the merits of their products. But they do.

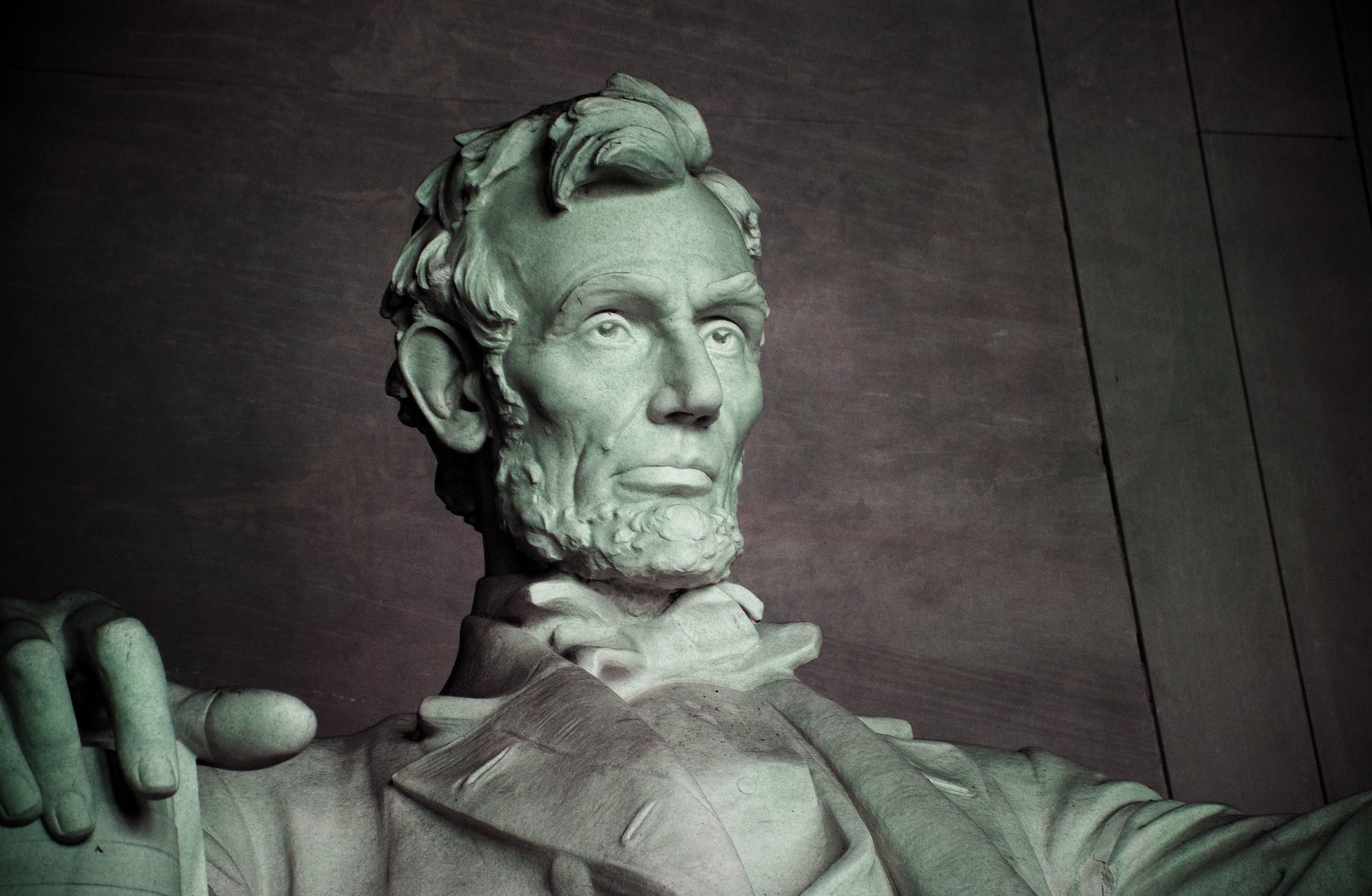

Of course, in every message, there has to be a base on reality. You probably heard the famous quote by Abraham Lincoln: “You can fool some of the people all of the time, and all of the people some of the time, but you can not fool all of the people all of the time.” In a nutshell: a company that actively invest in a product but lies about its performance will not go far.

The same thing happens with countries. Countries can promote themselves hiring advertising agencies who will communicate their beauties and virtues to the four corners of the world, as a touristic destination, as an investment destination, as a place for talented people to move to and develop a fruitful career. Still, it could be that this speech is just empty talk. The touristic facilities could be non-existent, the investments could be submitted to constant and arbitrary turmoil, and the scientists could see their research programs cut for lack of budget. In such a sad case, a promotional campaign equals to throwing the money away. What is even worse: once the public is aware of the deficiencies of a product, it becomes challenging to recover their trust.

Do not promise if you cannot deliver. This teaching is an excellent principle to adopt when promoting something.

Still, what about the other way around? Suppose that the buyers consider a product is of high quality. Should this good reputation have a direct effect on the competitiveness of this product? And the opposite: could a product that is considered competitive, benefit with a general positive aura qualitywise (which will cover any eventual defect)? Will we infer that all Volkwagen are good cars because they are branded VW or that any product manufactured in Germany is better because they show the stamp “Made in”?

In the last days I was talking to a friend working in a sanitary firm in Germany. They are selling millions of Made in China masks against COVID-19. “But now we are installing a in-house masks production line. Our masks will be 5 or 6 times more expensive than the Chinese ones, but they will be Made in Germany. We already have hundreds of thousands of orders in hold from our clients who prefer locally made product”. These masks will be more competitive despite the much higher price.

While looking online for papers that could analyse the relationship between competitiveness and perception, I fell upon the essay “The impact of the national competitiveness on the perception of corruption” by Simona-Roxana Ulman (2015, Elsevier). The author concludes that there is a strong correlation between

a) the competitiveness of a country, and

b) the perception of national corruption that citizens of that country have

According to the author:

“The aim of this study is to analyze if corruption perception is influenced by national competitiveness and to show the nature of this influence. This means that the standard of living, the rate of employment, the productivity, the commercial equilibrium, the national attractiveness, the ability of objective implementation, the flexibility and ability of sustaining growth which define the national competitiveness concept influence the way of perceiving the actions and the strategic behaviors of the public institutions represented by their public persons.” “The results indicated that a strong connection between GCI (Global Competitiveness Index rate) and CPI (Corruption Perception Index rate) really exists where the variation of the GCI variable explicates 74,3% of the CPI variation.”

This idea is extremely interesting because it shows that a measurable fact such as competitiveness, which results from multiple factors, some being numeric results and some being perceptions, mirror into an essential social quality: the level of corruption.

The syllogism is straightforward. Let’s consider a very competitive country. Its citizens can think:

Premise number one: “In my country, there is a high level of prosperity, and there are opportunities for all.”

Premise number two: “Corruption has a broad negative effect on the economic development of countries and reduces general well-being in the advantage of a few.”

Conclusion: “In my country, there is no corruption.”

The same, with opposed premises, could be made by the citizens of low ranked competitive countries, and the conclusion would be correct.

When talking about companies and products, things do not change much. When speaking of a firm or product, corruption would be a hidden deficiency that seriously affects its quality and possibilities of delivering in the long term:

Premise number one: “This company seems to be doing great. It meets its clients’ expectations, and all stakeholders are happy. It is very competitive.”

Premise number two: “Companies that are not behaving correctly with clients and stakeholders cannot be competitive.”

Conclusion: “This is a good and serious company to buy from and to collaborate with.”

Indeed, this is not always true. There are countries that, despite their immaculate appearance, keep scheletons in the closet. There are companies that, behind their influential and respected marks, have hidden famous corruption cases. But even in these circumstances, the surrounding reputation is of vital importance: the same law offence, when performed by a company from a country with a poor competitive score, will be judged much more severely than when performed by a firm from a state in top of the competitiveness index.

These different judgments might seem unfair, but this is the way perception works.

My conclusion is that, despite their different sizes, and natures, very similar principles will rule the competitiveness of a product, of a company and of a country. Our perception plays a basic role in the makeup of our judgement, also when we consider competitive companies or countries. The construction of perceptions is mainly a marketing job and it can be managed for some time, while the prevalence of perceptions in longer periods of time will depend on the fulfilment of expectations.