The 2nd Quarter Competitiveness Report (Informe trimestrial de Competitividad) issued by the Spanish Ministry of Industry, Trade and Tourism has appeared.

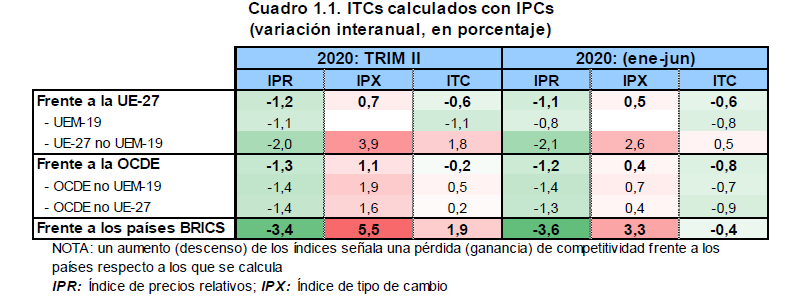

The summary to be found on page 6 establishes a small gain in competitiveness vs the European Union (0.6%), a more modest gain vs OECD countries (0.2% in global, thou -0.5% vs countries non in the Eurozone and -0.2% in countries non-EU) and a net loss vs BRICs of -0.5%. In a line: The Spanish industry slightly gained competitiveness mainly vs other Eurozone countries (Spain’s most important market) but lost competitiveness vs the rest of the world.

The revalorization of the € vs other currencies played a negative role in this evolution and explains a part of it.

This small improvement is good news, mainly when compared to the previous quarters in which, one after another, Spain had lost industrial competitiveness vs the Eurozone members. As said in the report (page 15):

“From January to March 2020 export prices diminished in several countries in the Eurozone: Greece (-5.8%), Finland (-2.3%), Luxemburg (-1.1%), Lithuania (-1.1%), Latvia (-0.8%), Portugal (-0.4%) and Cyprus (-0.2%). In Spain, the prices increased by 2.1% vs the same period in 2019. The prices also increased in Italy, Germany, France and the Nederlands in 2.5%, 2.5%, 2.2%, 0.1%, respectively”

Competitiveness in this study is simplified to a question of price. I have mentioned, in other articles in this blog, that the selling price of a good is a good measure of competitiveness. The selling price adds up the effect of the rest of factors participating in the production of that good. All efforts should be put in increasing the productivity of the factors of production when possible and costs in the other cases. But to do this companies need capital.

One of the most critical factors of cost in industrial production in Spain, absorbing large amounts of capital, is human resources. In this chart of the 2013 PWC report “Claves para la competitividad industrial española” (Keys of the Industrial competitiveness in Spain) we find a table that most probably is still valid as a general guideline:

This chart shows that HR cost accounts for 15.9% of total expenses or 38.8% when not considering the cost of raw materials. It is a very significative %. Even small variations of this % will have a meaningful impact on the total selling price and hence, on the overall competitiveness of the industry. So it should be sensible to think that salaries should show moderation to support competitiveness.

It would even be reasonable to expect that, in a country with such a high unemployment rate as Spain, wages would be submitted to a pressure downwards.

Nothing of this has happened, and the Spanish Government (s) have been acting against any logic in this regards.

In this table it is to be seen the minimum wage salary evolution in Spain: It increased by 22% in 2019 and an additional 5% in 2020:

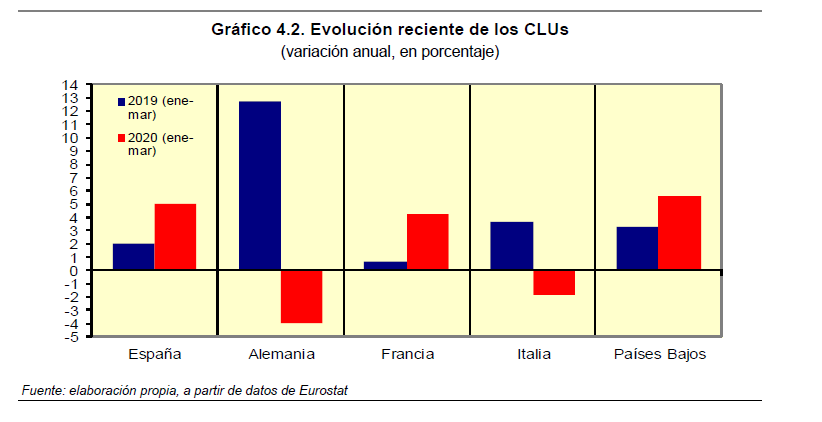

At the same time, the report from the Ministry of Industry which dedicates a particular analysis to the salary evolutions in the different countries (recognizing, therefore, its importance) shows how Spain has had, in 2020 the highest growth in salary costs: 5%.

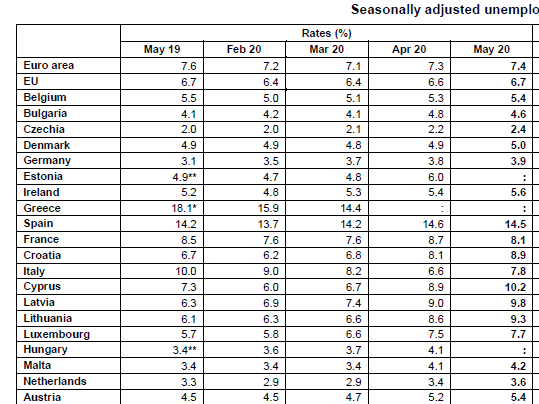

And this in a country with one of the highest unemployment rates in the OEDC:

So, in Germany, with a 3.9% unemployment salaries fall. In Spain, with 14.5% unemployment, wages grow 5%. As my father would say in Catalan, “Això, qui ho entén?” (Who can understand this?)

How is it possible that, in a country with very high unemployment and competitiveness issues, the Government itself sabotages the economy? It has no economic explanation. Only selfish political interests can explain this huge mistake.

Those defending the right of workers to get decent salaries have a point, of course. Everyone should aim for a correct life quality. But the first right of any person is to have the possibility of getting a job and no matter how hard we try, the laws of the market will tend to compensate any irregularity, and fixing excessive minimum wages is, in this case, a serious irregularity.

The private sector is the primary generator of employment, and the Spanish private sector cannot cope, in many cases, with those minimum wages. The result is no jobs.

Wouldn’t it be better to give some freedom to the market to regulate itself? If the companies could pay lower salaries, there would be many more contracts (and not so much people in the black economy, more income for the State). With fewer unemployed people salaries would slowly grow, firms could dedicate more resources to upgrade their capacities, to finance R&D and to the promotion and sales of their products.

The Spanish case is, to me, a perfect example of the very negative influence of politics in the correct economic evolution of a country. Politicians will talk about support for companies, competitiveness long term goals, fight against the black economy and, of course, the always sacred unemployment reduction goals. They will only act on their personal interest.

A thoughtful industrial and economic policy would look at the long term wellbeing of the people, and not only to the governing party reelection.