The COVID pandemic and the war in Ukraine have strengthened the European feeling that something is wrong with our production and supply model. Too much of our well-being has been trusted to manufacturing and delivery from third countries, mainly in Asia. This trust, if ever deserved, has proved illusory in the light of late events.

We all remember some recent very stressful situations: the difficulties of obtaining sanitary masks when most needed, the lack of mechanical ventilation units as people were dying in line in hospitals. Many voices rose, claiming that the European Union companies had gone too far in delocalizing their production to China or Southeast Asian countries. Another example is the lack of semiconductor chips for integrated circuits, which has fully impacted our economies at the macro and micro levels.

Some of these problems have been solved (masks and mechanical ventilation not being so much in need now), but others are distant from ending. We see new issues adding one on top of the other as the world has entered a new instability time that will probably prolong in the future.

The war in Ukraine has challenged our reach to something as basic as energy. The stable supplier-client relationship established with Russia by many Central and Eastern European countries is currently seriously damaged by the aggressivity of Mr Putin. For example, Russia has cut the gas supply to Poland and Bulgaria for not paying in the ruble. However, still, European citizens lean toward boycotting Russian imports of gas and oil to stop financing Putin’s war on Ukraine. This measure, if taken, would lead short term to a severe economic downturn that some governments, especially Germany’s, are not willing to accept.

At least since 2014, when I first wrote an article on the need to reindustrialize Europe based on some US studies on the subject, the idea of bringing industry back has been on the table. Asia was, and still is, the factory of the world, but the advantages of producing in Asia are not clear anymore or have disappeared: labour costs are still cheap compared with many countries in Europe, but the expenses linked to renting industrial sites, freight, customs and the political risks that have been spotted in the last years should push us to reconsider production within EU borders.

Few countries in Europe have the possibilities that Romania can display to become the new production hub in Europe.

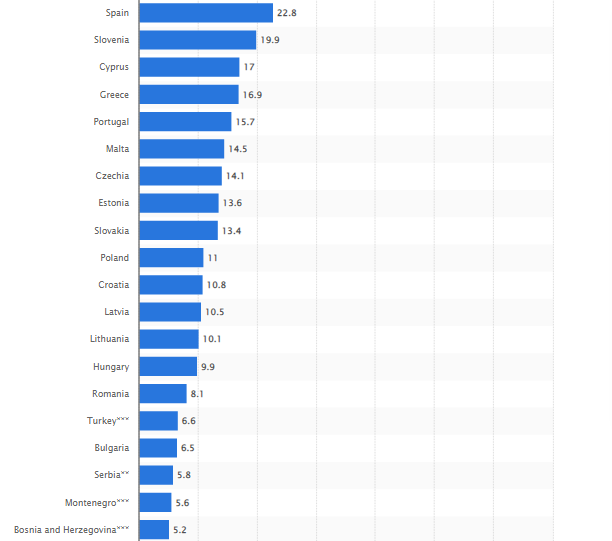

- When the question is about labour costs, Romania is still among the lowest in the region (source for the graphics Statista).

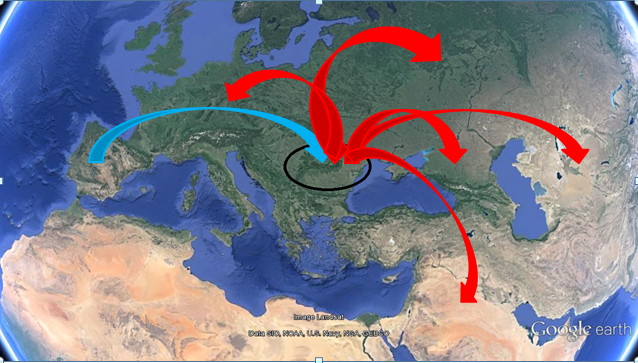

- Distance is not an issue. Freight between any part of Romania and Central Europe should not take more than 24 hours.

- Low taxation is an important reason for the move. Macro-economic stability should guarantee the maintenance of a low taxation scheme in the following years.

- Romania’s culture is European culture. Therefore, expatriates moving to Romania immediately adapt to the new environment and live within a 2-3 hours flight from home.

- At the same time, Romania’s position permits easy imports and exports from and to Central Asia, accessing a new market with millions of consumers with growing acquisition power.

- The legal frame is secure and political stability within the democratic rules has been a constant in the last years.

- There is already a long experience of many industries manufacturing in Romania in the last decades, many of them obtaining very positive results that support the arrival of new projects.

- Personal security is high.

- International schools and private clinics are valuable complementary assets to public facilities.

- The ability of locals to speak foreign languages, mainly English, is well known. However, French, German, Italian and Spanish are other languages easy to find among job applicants.

- Life costs are still reasonable in areas such as lodging and free time. Even in well-developed cities such as Timisoara, the real value of a salary in Romania is much higher than in other parts of Europe.

- The largest cities are pleasant and offer many moments of

- The main macroeconomic parameters are in excellent shape. The country has a very low public debt when compared to its peers.

- …

The list could continue.

There is, of course, another list, the list of points that need to be improved. Some of them are the following:

- Lack of workforce: four million people left the country in the previous years, most of them at the age of being employed. Unemployment is extremely low. Companies suffer in covering vacancies, mainly in cities.

- Infrastructures are not at the level expected for an EU country, mainly when it is now 15 years after Romania’s admission to the club. Moreover, freight within the country is slow, complex and sometimes expensive.

- Small corruption, mainly at the local level, hugely damages the country’s reputation and reduces investors’ interest in considering Romania as a possibility.

- Often public officers are not well prepared to deal with serious investment plans. Other times they do not see the good that such investment would bring to their municipalities in the medium and long term, only considering the short term impact that often does not prove interesting.

- There is no developed culture of cooperation among different political parties in power. Each politician will look at their self-interest, sacrificing the common good for the reelection. Paradoxically, the common good is usually a guarantee for reelection.

- The exchange risk exists not using the Euro as currency, and financing costs are much higher than in the Eurozone.

- The existence of a populist, nationalist party troubles the Romanian political scene. Their growing presence could represent a future problem for the composition of EU friendly governments. The same happens in other countries on the continent.

- …

It is the time of Romania. Romania has an excellent chance to value all its strong points, correct the weak ones, present the result with confidence on the international scene, and become a manufacturing base for EU companies.