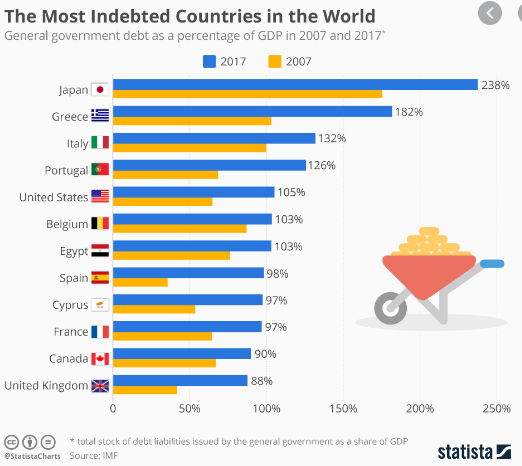

The Covid-19 pandemic will result in a notable increase in public debt in many countries for 2020.

Debt reflects what people, companies and countries spend today but will pay in the future, reducing our capacity of spending in the years to come. When the loans that account for the debt are used for profitable investments, the debtor can expect to return the loan and keep the profit. But in the last years, we have seen consistent growths in public debt motivated by a political interest more than by economic logic. In this case, the debtor will have trouble to repay the loan, and future generations will have to live with higher taxes or governmental austerity the consequence.

The repayment of public debt and interests implies the extraction of resources from potentially productive activities, either because companies suffer a tax increase, or because the government will not dispose of that money for productive investments.

Some voices claim that public debt is not a cause of worry because it is continuously refinanced and does not need to be paid. This opinion appears in the article “Everything You’ve Been Told About Government Debt Is Wrong” by Frances Coppola for Forbes (2018). In this scenario, governments should only worry about maintaining their capacity to pay the interest of the debt. The fact is that the interest rate that creditors will ask for their loans is linked to the level of confidence that debtors will offer. When a country can only provide low levels of assurance on their future economic performance (because of permanent public deficits, low growth, populism, their incapacity of paying due interests,…) the interest rates required by the market will grow. So, while the conclusion of the above listed Forbes article “…for the large sovereign countries examined in this paper, there is no reason to impose any more austerity on your populations. Throw off your hair shirts and invest in your economies.” (in other words, do not fear indebtment), sounds very attractive, it has a weak point: it presupposes that governments will place the funds into profitable investments that will benefit their economies and future generations. The reality is that many governments have burned billions in propagandistic and inefficient projects for their good and that of the parties they represent.

economies. This could cause the increase of interest rates and greater

difficulties to the repayment of debt.

The World Economic Forum considers the evolution of individual countries’ public debt in Pillar 4. Macroeconomic stability sector 4.02 “Debt dynamics: Index measuring the change in public debt, weighted by a country’s credit rating and debt level in relation to its GDP” (Global Competitiveness Index 2019, page 619). It is just one value among more than 100. Its importance seems quite mitigated. This actuality should give the reason to the defenders that debt does not matter much.

Others instead believe that growing public debt damages a country’s competitiveness. In the paper “Government debt and Competitiveness” signed by Robert S. Kaplan and David M. Walker for Harvard Business School, U.S. Competitiveness Project (2013), the authors put, in page 15, their finger on the problem “Every trillion dollars we borrow today, even at a zero interest rate, requires higher mandatory interest payments when the U.S. Treasury inevitably refinances the debt in the future, at much higher interest rates. If the future interest rate is, say 5%, then every $1 trillion borrowed today adds $50 billion per year to future deficits. This is an extra burden on future government’s ability to invest for competitiveness and higher living standards.”

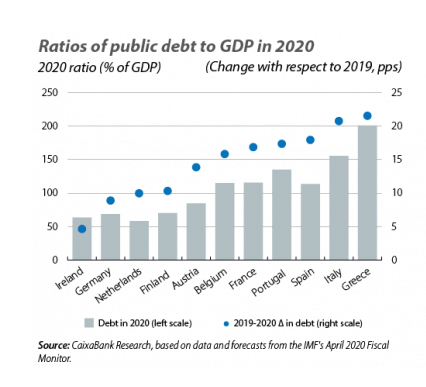

had low levels of indebtedness before the crisis have increased

debts much less than those with high levels before the crisis.

More debt equals more interests to be paid and fewer resources available for productive investments that would make the country competitive. It does not matter much if money is currently cheap. It could be more expensive in the future, and the burden would be much heavier to carry.

Anyone who has received a loan in the past knows very well how burdensome the interests can be and how much money they give away every year just in their payment, cash that could be used for more profitable or pleasant things instead. Why should it be different for a country?

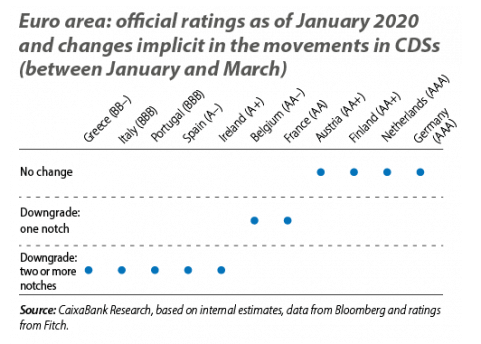

The two immediate charts above appear in the paper “Should we be concerned about the sustainability of public debt in the euro area?” by Adrià Morron Salmeron for La Caixa Research (2020). The author shows how differently the pandemic will hit the various Eurozone countries, and how a high indebtedness before the crisis is followed by more significant debt growth. The consequence will be a loss of confidence by the markets and higher spreads when refinancing the debts.

Another study looks at the matter from the opposite perspective. For instance, the paper “Competitiveness and Public Debts in Times of Crisis“, by Thomas Poufinas, George Galanos and Pyrros Papadimitriou (2018). This study analyses whether a country’s competitiveness impacts on its capacity to increase its public debt, or affects its citizens capacity to obtain credits. Their conclusions are clear: “The competitiveness of a country is vital both for the public and private debt. …. In this paper we were able to show that the public and private debt is definitely linked to the country competitiveness as measured by GDP growth, GDP per capita, ease of doing business, tax rate, pensions and unemployment, as evidenced by the regression analysis performed, comparing the relevant figures of our countries of interest.”

The year 2020 will be marked by the COVID-19 pandemic. The current increase in indebtment might be necessary, but debt offers more minuses than plusses. The growth of the debt that it infers will drag down our capacity to maintain future levels of investment, progress and wellbeing. It will harm our countries’ competitiveness. This will not identically affect all countries. Those who showed low indebtment levels will be able to overcome the situation much easier than their peers with high levels of public debt.