According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, a subsidy is “a grant by a government to a private person or company to assist an enterprise deemed advantageous to the public.”

The environment secretary of Mr Boris Johnson announced last Monday a plan to end agriculture subsidies in Great Britain. The transition process will last seven years. During this time, the British farmers will have to make an effort to adapt their productivity and gain competitivity. For sure, they will.

I do not normally congratulate Mr Johnson for anything, but this now I really want to applause this decision.

Since I read, a few weeks ago, about the very positive experience of New Zealand farmers, I was thinking of writing a note on the matter of subsidies. Not only related to agriculture, in general.

A small summary: In 1984, the New Zealand government eliminated all farm subsidies. The reason was that the country was in serious crisis and had to make savings. Despite the initial protests,

“When the subsidies were removed, it turned out to be a catalyst for productivity gains. New Zealand farmers cut costs, diversified their land use, sought nonfarm income, and developed new products. Farmers became more focused on pursuing activities that made good business sense.

Official data supports on-the-ground evidence that New Zealand greatly improved its farming efficiency after the reforms. Measured agricultural productivity had been stagnant in the years prior to the reforms, but since the reforms productivity has grown substantially faster in agriculture than in the New Zealand economy as a whole.” (source In New Zealand farmers do not want subsidies)

Only 1% of the agriculture companies dod not survive the cut. The rest adapted and flourished. They can be proud.

Subsidies, the way they are implemented in European agriculture, keep the business alive. Still, doped by the money inflow, they do not have much incentive to improve their productivity.

Let’s be clear; the money from subsidies does not grow in trees; it comes from the taxpayers. As Mrs Thatcher said long ago, there is no public money; there is taxpayers’ money. Some activities might need a push to start, but they cannot live on subsidies, they cannot become a load, a weight to the whole of the population. Not only it is not acceptable; it is also counterproductive for them all. Maybe the assisted sector will survive, but they will not evolve and will not improve.

I really celebrate the British measure. I hope that the European Union will follow the lead and cut subsidies which still represent 38% of the global budget.

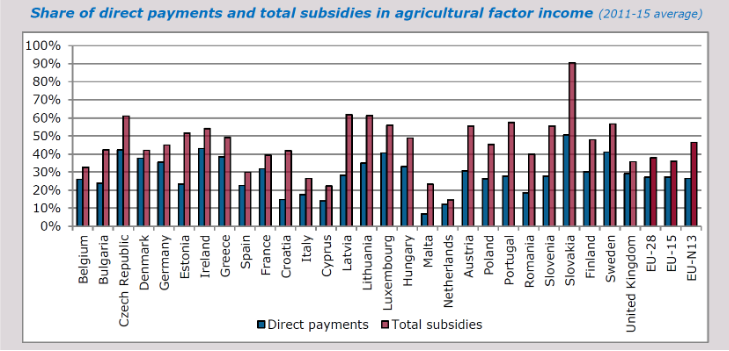

The situation is well described in the article “Measuring farmers’ dependence on public payments” by Alan Matthews

EU producers are highly dependent on public support (e.g. direct payments, rural development). The EU average share of direct payments in agricultural factor income in 2011-2015 stood at 27%. However, this masked considerable differences between Member States, ranging from 15% or less in Croatia, Cyprus, Malta and the Netherlands to more than 40% in the Czech Republic, Ireland, Luxembourg, Slovakia and Sweden. Taking all subsidies into account, total public support in agricultural income reached 38% of agricultural income on average in the EU.

The European Union is in a huge economic crises. What are our politicians waiting to present a similar plan to our farming sector?

Governments are also keen to use taxpayers’ money to buy votes, to content groups of voters, to pervert the system. This is done thru many different ways (increasing pensions and public salaries, benefiting some groups in front of others, contracting certain kinds of investment, buying the media, subsidies,..). This is utterly and equally wrong.

Let me give you a handy example (for me) of the negative effect of ongoing subsidies in a very different field: culture.

The best literature in Catalan was published during the ’50s and ’80s of the 20h century. Yes, exactly, during Franco’s regime in Spain. Maybe you are surprised, thinking that Franco was persecuting the Catalan language. This is false, Franco prohibited Catalan in the institutions, as Spanish had to be the only language in administration, as it is the case today of French in France and German in Germany. Still, for the rest, the people could speak Catalan or Spanish as they wished. I learned Catalan in the family and at kindergarten and school, from a very early age, and I was born in 1968. Franco was not giving ongoing subventions to the literature in Catalan, nor the literature in Spanish. The market decided who was a good writer (singer, journalist, actor,…) and who was a bad one. The best works in Catalan appeared in those years (by Pla, Rodoreda, Sales, De Pedrolo…) and were translated not only into Spanish but also into many other languages. The situation has changed since the democratic Catalan government has used taxpayers’ money to sustain a myriad of self-called artists which the only merit is to write in Catalan expecting in exchange their support for nationalism. Nothing outstanding has appeared in literature in the Catalan language in the last forty years, and it would be a huge surprise if something appeared. Why should it? To produce outstanding work, it is necessary to work hard, but why to work hard if the money comes anyway? In the meantime, the best Catalan writers write in Spanish (Mendoza, Vila-Mata, Ruiz Zafón, Falcones, Marsé, Cercas, Regàs, Moix,…) without any subsidies from any government. This is how a political decision results in an overall mediocrity that leads to the cultural insignificance of the Catalan language in the international scene.

That is the result of ongoing subsidies: the nothingness. And this is what European agriculture should avoid. Subsidies take money that taxpayers would use for something else and give it to sectors who do not use it to improve and remain addicted to it and dependent on external help.

We have all heard that to save starving people from poverty it is not enough to give them a fish, you need to teach them to fish. If you do not teach them to fish, they will survive on the free meals, but they will be a charge forever. We do not need to go to third-world countries to apply this teaching. Instead of giving fish to subsidised sectors, the institutions should use a part of that money to develop their management capacities, to teach them how markets work, to train them to compete in a free world.

Ongoing subsidies brake competitiveness and should tend to zero for really competitive societies.